Deep dive into the hypothesis that cell phone radiation, by lowering testosterone levels, might be nudging the political spectrum toward the Democratic side. The claim is controversial, speculative, and stands on the frontier between endocrine science, political psychology, and telecommunications policy. Yet the question itself—“Is cell phone radiation creating Democrats?”—invites an examination of how biological, technological, and social factors can overlap to shape our world.

Disclaimer:

This article is not asserting a proven causal relationship that cell phone radiation definitively creates Democrats. Rather, it explores the converging points of inquiry: (1) research on testosterone (T) and political preference, (2) evidence that electromagnetic radiation (EMR) from phones and wireless devices can reduce T levels, and (3) how government policy from the mid-1990s to the present may have facilitated widespread EMR exposure. The information herein is culled from peer-reviewed science, anecdotal reports, policy documents, and interviews where available. Readers should approach this intersection of biology and politics with healthy skepticism; correlation does not necessarily imply causation.

From Campaign Trails to Cell Towers

The United States is often described as a nation divided, politically polarized between red and blue, Republicans and Democrats. Pundits attribute this polarization to media echo chambers, gerrymandering, social media algorithms, cultural conflicts—yet few consider biological influences on political identity. Even fewer question whether the technologies that permeate modern life—namely cell phone radiation—might subtly shape that very identity.

This idea might sound outlandish: Could electromagnetic waves from our phones, Wi-Fi routers, and cell towers actually tip someone’s political leanings? Yet, surprising evidence from two parallel research strands—testosterone studies that link the hormone to political inclination, and microwave radiation studies that suggest lowered T levels—has given rise to a provocative hypothesis: If wireless radiation lowers T, and low T is correlated with a higher likelihood of being a Democrat, then the ubiquitous presence of cell phones might be contributing to “blue shifts.”

Regardless of one’s initial reaction, the question compels exploration. In this article, we step onto an investigative path, weaving scientific findings, policy background, and cultural commentary. Along the way, we’ll examine how the 1996 Telecommunications Act effectively shielded wireless expansion from health-based scrutiny, how the FCC’s guidelines may or may not be in sync with the latest science, and how a single hormone—testosterone—is entangled in the social tapestry of politics.

Testosterone and Politics: Why Biology Matters

For decades, political scientists assumed that voting behavior and party affiliation were primarily shaped by socioeconomic, cultural, and familial factors. But a growing field—biopolitics—asks how physiology and genetics might also color our ideological leanings. Several findings converge on the notion that testosterone in particular can influence traits like risk-taking, competitiveness, or group loyalty, all of which might translate into different political preferences.

Indeed, the idea that testosterone shapes behavior is not new. Studies have long associated T with higher aggressiveness, competitiveness, and even certain leadership styles. More recent work has examined whether T levels correlate with “tough-mindedness” or preference for more “conservative” stances in specific domains (e.g., law-and-order policies, national security). While such conclusions remain debated, there is an undeniable biological dimension to politics—one that works in tandem with environmental and social contexts.

Moreover, no hormone acts in a vacuum: men with lower T might exhibit different social or psychological dispositions, including changes in mood, energy, or risk tolerance. Some hypothesize that, collectively, these differences could manifest as more progressive or liberal views (e.g., support for wealth redistribution, emphasis on cooperation). Conversely, men with higher T might lean toward less government intervention and more personal autonomy. Though obviously not an absolute rule—plenty of progressive men have high T and plenty of conservative men have low T—the possibility that average differences might tilt population-level trends is enough to warrant further research.

Paul Zak’s Study on “Red Shifts” in Weakly Affiliated Democrats

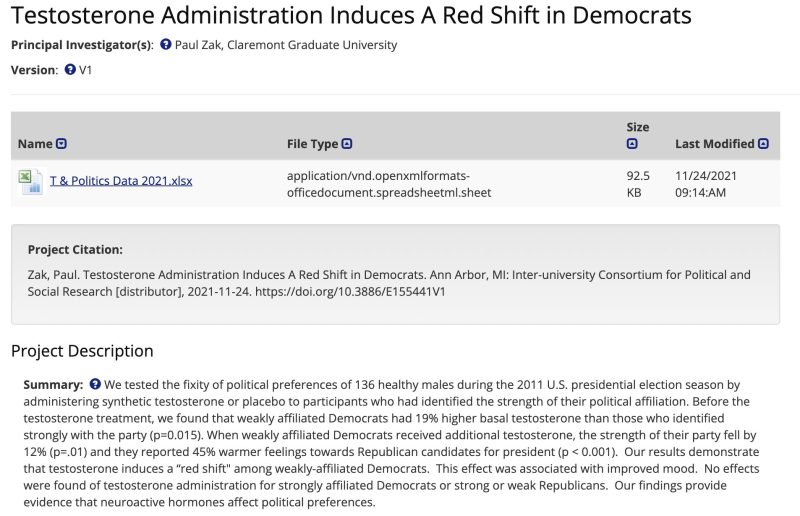

In 2021, an intriguing dataset was deposited at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) under the title, “Testosterone Administration Induces A Red Shift in Democrats.” Led by Dr. Paul Zak of Claremont Graduate University, the study tested the political preferences of 136 healthy males during the 2011 U.S. presidential election. Participants self-identified their political affiliation and the strength of that affiliation, then received either synthetic testosterone or a placebo.

Key findings included:

- Weakly Affiliated Democrats had, on average, 19% higher basal testosterone than those strongly affiliated with their party.

- When administered additional testosterone, these “weak Dems” showed a 12% decrease in the strength of their Democrat identification.

- They reported 45% warmer feelings toward Republican candidates.

The statistical significance (p < 0.001 in some measures) suggested a robust effect: giving more T to Democrats on the fence nudged them further from their party identity and closer to the GOP. Equally notable: the same intervention did not affect strongly affiliated Democrats or Republicans (whether strong or weak). While the sample size was relatively small, this study pointed to a possible relationship between T levels and political shifts among individuals whose affiliation was not deeply rooted.

Zak himself described the findings as evidence that “neuroactive hormones” can affect political preferences, particularly among those less steadfast in their partisanship. He stressed that there was “no effect” of testosterone on strong Democrats or Republicans—possibly because hardened ideologues are less swayed by short-term hormonal fluctuations. Regardless, the results generated conversation: if artificially raising T could “nudge” some Democrats to the right, could the reverse—lower T—nudge some men to the left?

This is precisely where speculation about cell phone radiation enters the picture.

Microwave Radiation and Hormones: The Evidence for Lower T

The second body of research fueling this hypothesis is the reported link between radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation (RF-EMR) from wireless devices and decreased testosterone levels. Although scientists still debate the extent of these effects in humans, a growing number of independent (non–industry-funded) animal studies suggest that chronic exposure to low-level microwave radiation can lower T and sperm counts, and disrupt the endocrine system.

Animal and Human Studies

Animal models provide controlled environments to measure hormone changes upon exposure to cell-phone-like frequencies (often around 900 MHz to 2.45 GHz). Results from rat studies consistently show that daily exposure over weeks or months can suppress testosterone or damage testicular tissue. In one systematic review, most rodent studies found significantly lower T after extended RF-EMR exposure, often alongside reduced sperm motility and heightened oxidative stress in the testes.

Human observational studies are more mixed, partly because real-life exposures are variable and confounded by lifestyle. However, at least one multi-year cohort (Eskander et al.) found that men who were heavy cell phone users exhibited a gradual decrease in T levels over time. Another retrospective study on men attending infertility clinics observed that phone users had a suppressed luteinizing hormone (LH) level, hinting at a disruption in the normal signaling that leads to T production.

It’s worth acknowledging that not all findings are uniform, and some studies fail to detect significant changes. Still, the balance of evidence over the last 15 years leans toward the conclusion that long-term, close-proximity exposure (e.g., carrying a phone in a front pocket all day) may lower T or alter male reproductive hormones.

Potential Biological Mechanisms

Critics sometimes argue that non-ionizing microwave radiation cannot directly damage DNA. But the proposed pathways are more subtle. Some scientists suggest thermal and non-thermal effects such as:

- Localized Heating: Holding an active phone close to the testes raises tissue temperature. Testicular function is highly temperature-sensitive, so even a small, chronic heat elevation might impair T production.

- Oxidative Stress: RF-EMR can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage cells if antioxidant defenses are overwhelmed. Testicular tissue can be particularly vulnerable.

- Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel (VGCC) Hypothesis: Proposed by Dr. Martin Pall, this model suggests that EMFs can overactivate calcium channels in cell membranes, causing intracellular calcium overload and a cascade of biochemical disruptions.

- Hormonal Regulatory Axis: Disruption to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis could alter signals that stimulate testosterone synthesis.

The possibility remains that if modern lifestyles ensure constant exposure—smartphones on our person, Wi-Fi routers at home, Bluetooth headsets, plus 4G/5G signals from cell towers—then cumulative effects might eventually contribute to lower T levels in a portion of the population.

Blue Light, Circadian Rhythms, and Hormonal Health

While the focus is on microwave radiation, it’s worth noting that nearly all our devices also emit large amounts of blue light from LED screens. Blue light can disrupt circadian rhythms by suppressing melatonin at night, which in turn can disturb the balance of other hormones—including testosterone. Research indicates that poor or insufficient sleep disrupts normal T production, especially in the early morning hours when T naturally peaks.

One could argue that cumulative modern habits—late-night phone use, screen time in bed, carrying phones in close contact, being bathed in Wi-Fi signals—form a perfect storm for chronic endocrine disruption. If testosterone is among the hormones most affected, an entire population might see their average T levels drift downward over decades. Indeed, broader studies suggest that men’s T levels in Western nations have steadily dropped since at least the 1980s, a trend attributed to lifestyle, diet, obesity, environmental chemicals, and stress. Now, wireless radiation may warrant serious consideration as yet another contributor.

Connecting the Dots: Could EMR Exposure Impact Political Affiliation?

The leap from “wireless radiation may lower T” to “EMR might create more Democrats” is enormous. One must keep the following in mind:

- Correlation vs Causation: Even if men with lower T levels happen—on average—to lean more left, that does not prove that EMR-induced T changes cause a shift to Democratic identification.

- Individual Variability: Each person’s political affiliation is shaped by myriad factors: upbringing, personal values, socioeconomics, peer groups, and media. Hormones might tilt edges, but few scientists claim hormones can rewire deeply held beliefs.

- Strength of Party Affiliation: Dr. Zak’s study highlights that only weakly affiliated Democrats were significantly swayed by extra T. Those strongly affiliated were unaffected. By parallel, one might guess that only men with moderate or milder left-leaning predispositions could be “pushed further left” if their T is lowered, and only if their personal environment is reinforcing those positions.

Despite these caveats, the notion still intrigues some. If the typical man’s T level is quietly eroding over time due to lifestyle and environmental factors, and if lower T correlates with certain psychological traits or political preferences, then perhaps society’s ideological balance is shifting, albeit subtly and gradually. This does not necessarily mean a man “wakes up Democrat” because he slept next to his phone. Rather, there may be a marginal push that nudges him left or dampens aspects of his worldview that would have otherwise leaned more conservative.

Such an argument remains speculative. Yet, it touches on something deeper: Human biology is in constant dialogue with the environment we create. If certain political tendencies revolve around risk tolerance, entrepreneurial spirit, or hierarchical structures, and those are partially governed by hormones, then the technologies that alter those hormones shape more than just our personal health; they shape the collective psyche.

The 1996 Telecommunications Act and Section 704

This brings us to the regulatory environment that has allowed the near-ubiquitous presence of wireless infrastructure. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act, the first major overhaul of U.S. telecom law in six decades. Tucked within it was Section 704, which, in simplified terms, preempted local or state governments from denying cell tower permits on the basis of health or environmental concerns—provided the tower met federal guidelines.

Opponents immediately criticized Section 704 for prioritizing rapid deployment of wireless technology over legitimate health and environmental worries. As the internet age blossomed, new cell towers proliferated across the country, each representing a localized node of microwave-frequency EMR. Those who suspected potential health risks, including scientists and local communities, found themselves with no legal recourse to block installations purely on EMR concerns.

Why is Section 704 important here? Because it effectively shielded wireless expansion from the sorts of public oversight that might have led to more cautious or limited rollout. By the time 4G and 5G arrived, thousands upon thousands of towers, antennas, and small cells were entrenched. This environment saturates Americans (and many others worldwide) with low-level EMR exposure. While the FCC sets exposure limits, critics argue these limits focus only on thermal thresholds (where tissue heating becomes unsafe), ignoring “non-thermal” effects such as hormonal disruption or oxidative stress.

The question, therefore, is: “Could that regulatory framework, established in 1996, have inadvertently triggered a mass experiment in which an entire population’s endocrine system is being tested? And if so, might that experiment have unforeseen consequences for politics?”

Policy, Industry, and the FCC: A Brief History

Fast-forward to the Obama administration: President Obama appointed Tom Wheeler, a former head of the CTIA (Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association)—the chief lobbying group for the wireless industry—as Chairman of the FCC. For critics of the 1996 Act, this appointment was emblematic of regulatory capture, in which the very industry meant to be regulated exerts heavy influence on the regulator. While Wheeler oversaw important net neutrality rules, some observers suspected the FCC under his leadership was still disinclined to revisit the science around EMR safety limits.

This pattern—where the telecommunications industry maintains close ties with regulators—has repeated for decades. The net result is that U.S. safety standards for RF exposure remain largely the same as they were in the late 1990s, despite an avalanche of studies suggesting possible biological effects below those thresholds. Many European nations and other countries have stricter limits, reflecting a more precautionary stance. But in America, industry lobbying and legal structures (like Section 704) stifle efforts to place tighter restrictions on tower placement or device emissions.

Is the outcome that we have unwittingly created an environment conducive to “low T,” thereby possibly swaying some men’s political dispositions? At the very least, the policy story sets the stage for the mass adoption of a technology that saturates nearly every facet of daily life—often without robust public debate on health ramifications.

Investigative Perspectives: Experts, Critics, and the Public

Expert Opinions

Hormone levels and political ideologies are subject to a swirl of complex influences, making single-factor attributions risky. Nevertheless, a minority of researchers in reproductive endocrinology, neurology, and public health argue that the evidence for non-thermal EMR effects is strong enough to warrant precautionary policies. They cite studies on sperm damage, oxidative stress in testicular tissue, circadian disruption from nighttime phone use, and the intriguing possibility that T-lowering over decades might have subtle sociopolitical consequences.

Political and Cultural Critics

Some political commentators from conservative circles relish the narrative that “low T equals liberal.” They highlight anecdotal stereotypes—like the “soy boy” meme or references to male feminists having reduced testosterone—and try to link these cultural caricatures to real biology. Many, however, overshoot the data by implying that all liberal men must have low T, an assertion that is not only unscientific but also belies the complexities of political identity.

Meanwhile, progressives sometimes dismiss these theories as conspiracy-laden or “anti-science,” preferring to highlight structural and cultural factors that shape politics. From their vantage, “hormones do not dictate ideology,” and focusing on T levels can overshadow socioeconomic explanations. Yet even left-leaning voices occasionally acknowledge the basic plausibility that endocrine disruptors or environmental pollutants could shift populations in unknown ways—though they might be more concerned with pollutants like BPA or pesticides.

Public Curiosity

Online, the question “Is cell phone radiation creating Democrats?” can quickly descend into partisan bickering or jokes. Yet behind the viral headlines lies an earnest curiosity about whether technology might shape us more deeply than we realize. The public’s appetite for any “gotcha” explanation of political shifts is high. But there is also a rightful skepticism toward sensational claims that overshadow nuance.

A Deeper Look at Potential Societal Consequences

Suppose we momentarily accept the premise that chronic wireless EMR exposure contributes, even modestly, to lower testosterone across a segment of the male population. If so, how might that ripple through society and politics?

-

Changes in Behavior and Mood

- Decreased T can correlate with reduced aggression, risk-taking, or competitiveness. Some data also tie low T to higher anxiety or depression. An entire population with systematically lower T might tilt toward cooperative or egalitarian norms—often (but not always) associated with progressive or “left” politics.

-

Reproductive Health Implications

- Reduced fertility is already a recognized concern in multiple developed nations. If part of that fertility decline stems from environmental exposures (including EMR), we might see demographic shifts—though how that aligns politically is less clear.

-

Political Engagement

- Could men with lower T be less likely to engage in politically charged conflict or street activism? Possibly, though real-world activism depends on moral outrage and ideological conviction, not just T levels.

-

Potential Reinforcement Loops

- If the policy environment remains unaltered—i.e., the FCC keeps guidelines largely the same, the industry continues to expand 5G networks—it might perpetuate the conditions that keep T levels suppressed, leading to a gradual drift in social norms and political leanings. Over decades, such a drift might appear subtle but could be significant at scale.

-

Skeptical Counterpoints

- We must note that in many Western societies, women also outvote men in raw numbers, and demographic shifts (in terms of race, age, and education) strongly influence election outcomes. Hormonal arguments are but one piece of a much larger puzzle that includes economic inequality, party platforms, candidate charisma, and historical events.

This portion of the discussion veers into speculative territory. Nonetheless, it underscores the potential magnitude of an issue if, indeed, technology is not biologically inert but actively shapes endocrine function.

Conclusion: Shifting Frequencies, Shifting Politics?

A quarter-century ago, few could have predicted that the Telecommunications Act of 1996—and its notorious Section 704—would lead to an America dotted with hundreds of thousands of cell towers. Nor could they foresee that billions of people worldwide would soon carry potent EMR emitters in their pockets all day, every day. The policy decisions made in the mid-1990s privileged rapid wireless deployment over precautionary review. And while the benefits of a connected society are undeniable—economic growth, global communication, instant access to information—unintended consequences deserve attention.

On the biological side, scientists like Dr. Paul Zak have demonstrated that testosterone can influence political affiliation—or at least warm some men toward conservative candidates. Others, via rodent and limited human data, have linked wireless EMR to lowered T. If both lines of inquiry hold even partial truths, then it is conceivable that the electromagnetic saturation of modern life fosters an environment more favorable to left-leaning political leanings over time. Or, put differently, a general “T dampening” might reduce the subset of men most primed to align with right-leaning ideologies—especially among those who are not deeply entrenched partisans.

Whether that spells an emergent “blue wave” or simply a small nudge in a complex tapestry of factors remains unknown. Indeed, the synergy of environment and biology is rarely so clean-cut. Furthermore, ideology stems from numerous psychological constructs—empathy, fairness, tradition, fear of change, economic interests—none of which can be pinned solely on a single hormone.

Still, the question “” is sufficiently provocative to merit more than just dismissal. It speaks to the broader oversight that often accompanies technological revolutions: as we embrace each new wave of innovation, from cell towers to 5G to “smart everything,” we do not always weigh the potential long-range impacts on health, society, and culture. Instead, the default assumption remains that if a technology is not acutely harmful, it is safe enough.

The path forward may involve a few steps:

- Funding and Conducting More Independent Research: Studies free from wireless industry influence can explore the relationship between EMR exposure, hormonal health, and long-term outcomes, including shifts in attitudes or behaviors.

- Revisiting FCC Guidelines: Regulators might consider the emerging evidence for non-thermal biological effects and update exposure limits accordingly.

- Modernizing Section 704: Re-examining the Telecom Act to allow localities some health- or environment-based input on tower placements could ensure more balanced infrastructure development.

- Individual Precaution: Meanwhile, men concerned about fertility or T levels can adopt simple practices, like using speakerphone, reducing direct phone-to-body contact, turning off Wi-Fi when not in use, or limiting nighttime screen exposure to preserve healthy circadian rhythms.

Any synergy between technology and politics will likely remain an unfolding narrative. Perhaps the core lesson is humility: we live in a dynamic ecosystem, and small, incremental influences—from chemical pollutants to social media echo chambers—can gradually reshape human behavior and society. As one commentator quipped, “If microwave towers or cell phones do even slightly lower T, and if T does even slightly influence ideology, then maybe the biggest hidden political influencer of our age is not an election campaign or a social media giant—but the constant wireless hum that pervades our lives.”

Final Thoughts

To be clear, a direct, proven link between cell phone radiation and shifting from red to blue remains speculative. But for those attuned to the subtle interplay of biology, technology, and society, it is a line of investigation that begs further scrutiny. If we fail to ask questions—about how our devices affect us or how policy from 1996 might be shaping 2026—we risk missing a slow-moving revolution in human behavior.

In the end, maybe the real story is not that cell phones alone are turning the country blue, but that we, as a society, have set ourselves on a course where entire generations grow up breathing an “electromagnetic air.” Whether that invisible factor fosters social cooperation or undercuts certain conservative impulses is an open question. But given the stakes—both for public health and the democratic process—surely it is worth more than a cursory glance. After all, the difference between conspiracy theory and forward-thinking caution sometimes lies in how willing we are to explore the evidence without prejudice.

And so we come full circle, to ask: If we can artificially raise a weak Democrat’s testosterone and watch him drift red, might we, by artificially suppressing that hormone (through pervasive wireless exposure), be gently steering populations the other way? At the crossroads of technology, biology, and politics, the signal is strong, but the science remains incomplete. It is up to us to tune in and decide how best to respond.